This is not far back in time, and Willie even looks so young, unlined face, navy blue track suit and Kangol hat. Yet it’s hard to recognize the nearness of his experiences, and many tend to view this as a remote past, one that has been overcome. “Just get over it,” some say, at sites where such histories and memories are represented. “I didn’t live then, so it’s not my problem,” and “Why bring all that up again, it’s too painful...black citizens should get over it,”[2] are a few reactions to sites that represent the history of slavery or the struggle for civil rights 1“We refuse to sit upon your stool of everlasting repentance,”[3] they said in Savannah in 2002. “An anti-white exercise in shame and blame,” and “a threat to…faith in Southern heritage, American tradition, culture and glory,” they said in Wallace Louisiana in 2014.[4]

“They should just move on.” Willie has. He moved to Alabama where “US Steel ran the state,” where they recruited him to be a manager at BellSouth, even though it was a difficult place for black people to be at the time, Birmingham was, “where all that nonsense was going on.” Today US Steel still owns large tracts of land in Alabama, about 150,000 acres as of 2011.[5] Today Willie is a big supporter of America, “of what it currently has become.” Only here, he says, can it happen. “I was born in the slums, and all my kids have advanced degrees.” He has moved on, but can we?

Is forgetting really possible? In his essay on the Use and Abuse of History, Nietzsche writes:

For when [the] past is analyzed critically, then we grasp with a knife at its roots and go cruelly beyond all reverence. It is always a dangerous process, that is, a dangerous process for life itself. And people or ages serving life in this way, by judging and destroying a past, are always dangerous and in danger. For since we are now the products of earlier generations, we are also the products of their aberrations, passions, mistakes, and even crimes. It is impossible to loose oneself from this chain entirely. When we condemn that confusion and consider ourselves released from it, then we have not overcome the fact that we are derived from it.[6]

He points to the impossibility of forgetting, of disconnecting from an unwanted historical context, where even the forgotten is intricately interwoven, collectively, with our cultural selves. For Lyotard, certain “excitations” are so troubling that they cannot be processed or dealt with. They do not even enter or affect consciousness; they are not introduced and remain “unpresented” as a “silence which does not make itself heard as silence.” He refers to a “reserve” that retains this memory “without consciousness having been informed about it.” It “lies in the reserve in the interior hidden away…”[7] Thus, what has been ‘forgotten’ is always held in reserve - whether we would have it or not. Ricoeur argues that “the most troubling experiences of forgetting…display their most malevolent effects only on the scale of collective memories.”[8]

I suffer, we all suffer, because of this neglect, this ambient obscurance, this obsfuscation. It affects us all, and it is impossible to loosen this chain. And here our great country, against our will, rewrites the narrative.

The resource of narrative then becomes the trap, when higher powers take over the emplotment and impose a canonical narrative by means of intimidation or seduction, fear or flattery. A devious form of forgetting is at work here, resulting from the stripping of social actors of their original powers to recount their actions for themselves.[9]

Blame, guilt, shame is pushed on to the South. An other place, different from here. We revel in the great myth of American blamelessness, as expressed at our monuments at Ground Zero and at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. These are sites of great tragedies, of enormous scale and consequence, but they are also sites of a performance, whereby we “legitimize American blamelessness,” where the deaths of innocent victims are marshaled to “legitimate national security narratives of revenge and retribution…”[10]1The deaths of these innocents are still being used today to justify exclusionary policies that seek to limit immigration, and even travel. Even the much-lauded Vietnam Veterans Memorial has been criticized as a site of highly selective memory and forgetting. As a veteran of the war stated, “Our healing here is therapeutic, but not historic…The memorial says exactly what we wanted to say about Vietnam…absolutely nothing.”[11]2 Neither of these sites takes a critical stance on what happened or why. We point, as always, to the innocent victims who died. We are blameless; the guilty parties are elsewhere.

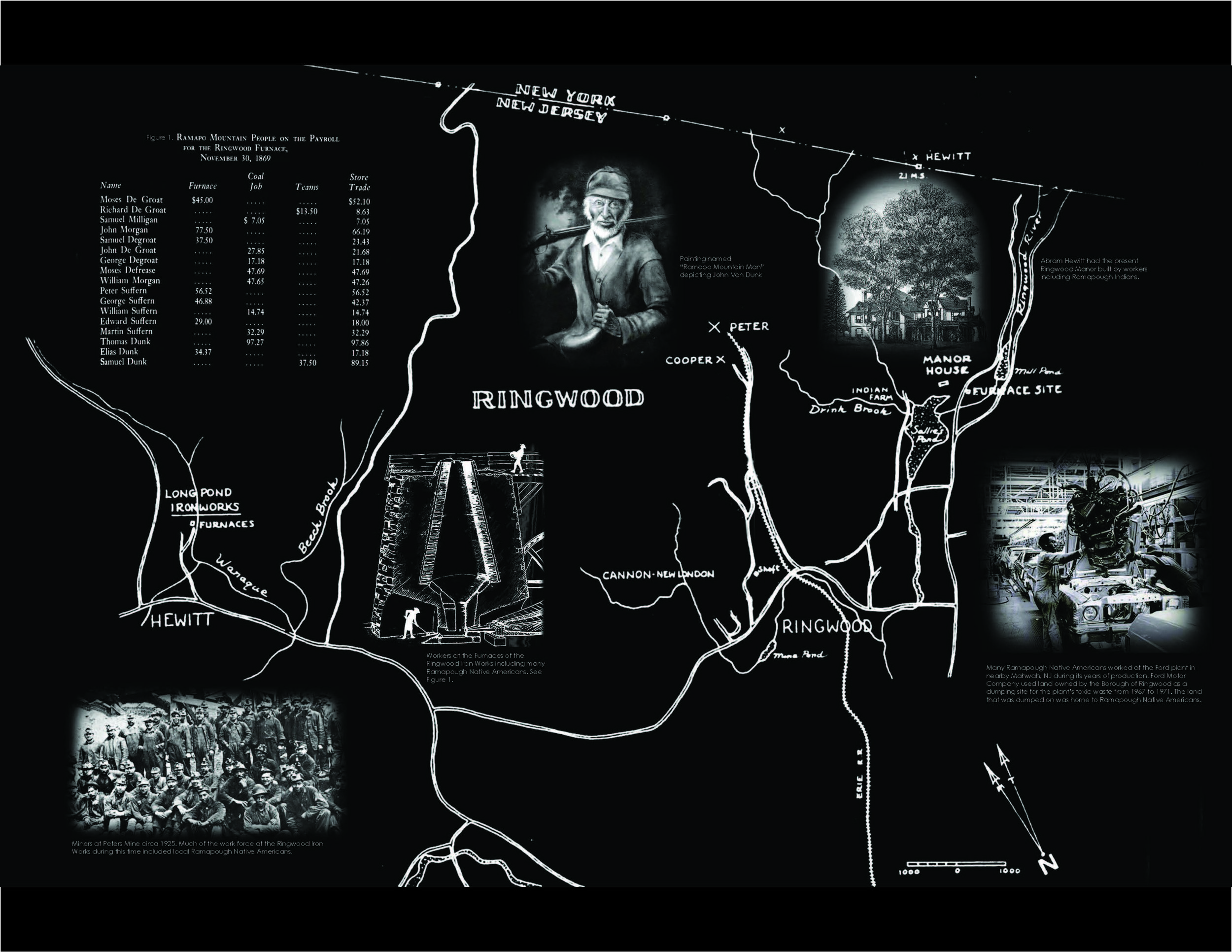

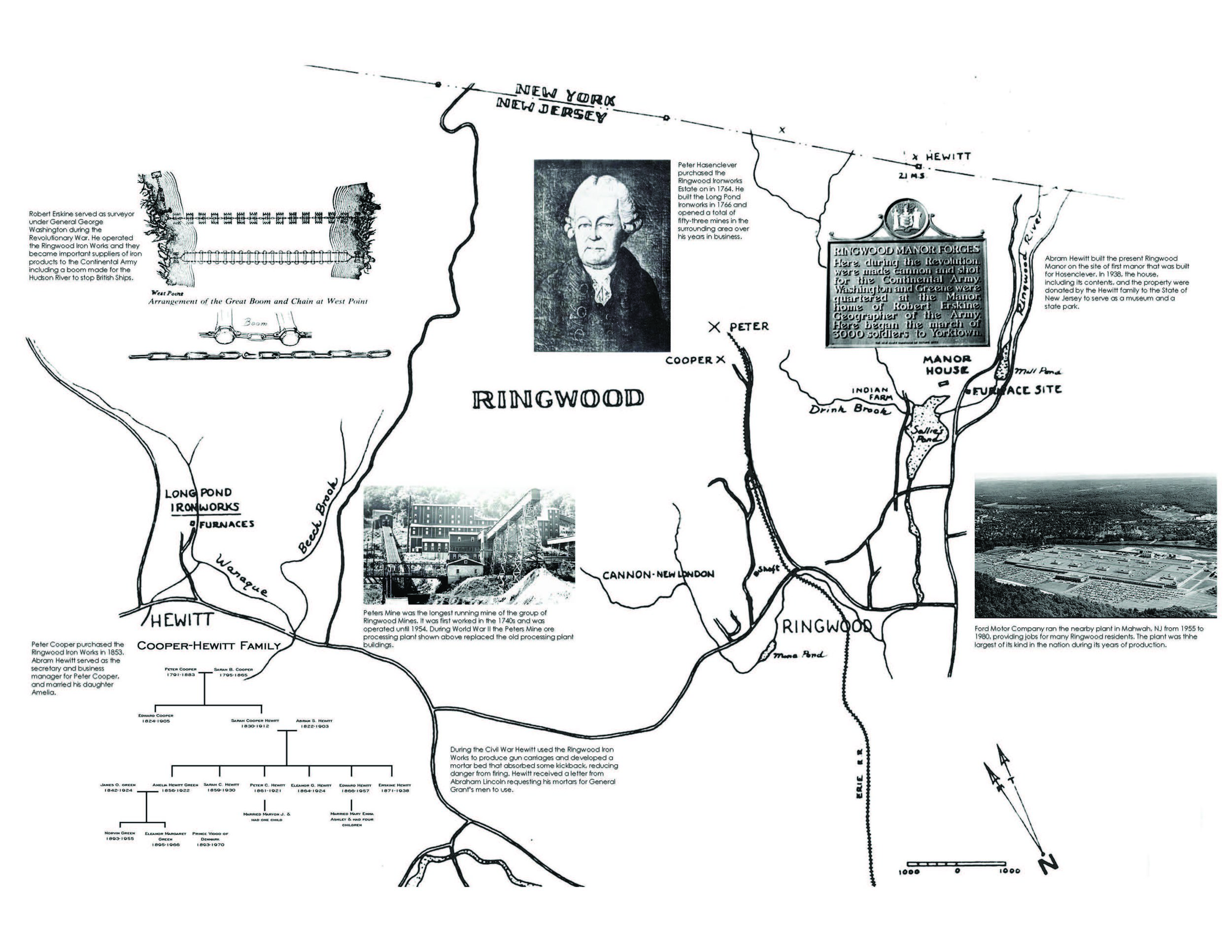

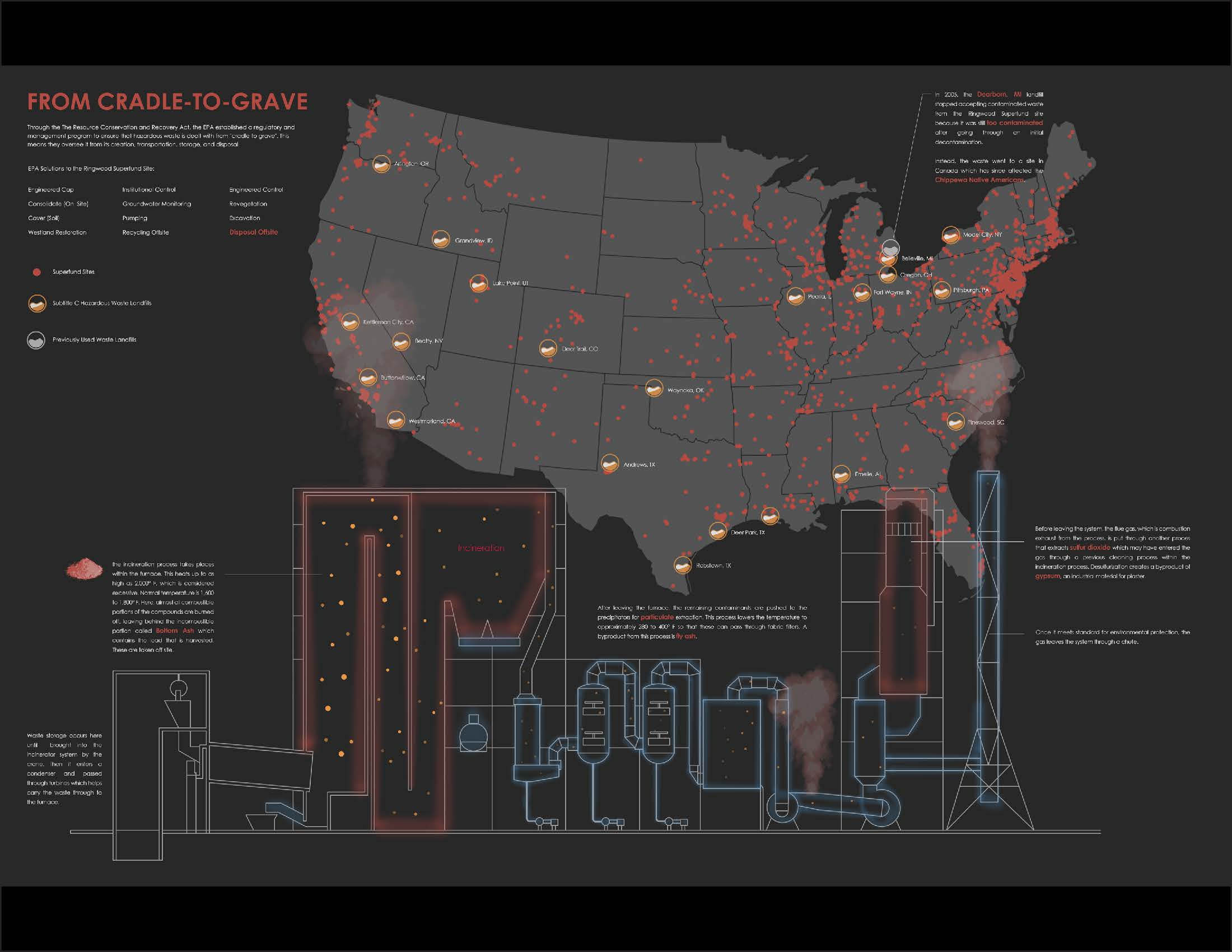

We forget the retreat after the 1870s, the allowance of the institution of Jim Crow laws, Plessy vs. Ferguson, “…the long and violent hangover after the Civil War when the South, left to its own devices as the North looked away, dismantled the freedoms granted former slaves after the war.”[12] This forgetting is required so that we can maintain the right to impart blame to an other place. In this forgetting we all become trapped in the narrative, not realizing that it is not possible to tell the story of ‘here’ without also telling the story of ‘there.’ It is not possible to tell the story of the North without also telling the story of the South. It is not possible to tell the story of my father in Chicago without telling the story of Kansas. These histories echo across landscapes, connecting places like Alabama and St. Louis, Mississippi and New York. Fragmenting and compartmentalizing these into neat narratives does not work. Whether addressed or not, they echo throughout the American landscape, taking measure of our progress, of our past. It does no good to try to impart this past to an other place, a foreign way of life, from a ‘now’ to a ‘then.’ All the things and people that make our America possible carry these echoes with them, through the economic drivers, through the “sacrificial landscapes”[13] from which we extract resources: mineral, cultural, human.

Distancing in time is mirrored by a distancing of place. Today another kind of geographical forgetting occurs, as other uncomfortable realities are ignored, tucked away, far out of sight. Today we forget Louisiana, bayous destroyed by oil, the leaks from great underground salt domes, that we don’t even know exist, giant hidden caverns the size of huge monuments to geological processes, but also to industry, progress, economic development. The Napoleonville Dome, three miles wide and one mile deep, lies below the earth under a layer of oil and natural gas. Here 53 caverns are owned by petrochemical companies, who rent out space, caverns, where chemicals and brine are stored. One was punctured as Texas Brine was drilling deep inside it in 2012.

When the drill pierced the side of one cavern inside the dome, a catastrophe slowly unfolded. Weakened, one wall of the cavern crumpled under the pressure of the surrounding shale. Water was sucked down, drawing trees and brush with it. Oil from around the dome oozed up. The earth shook. In places its surface tilted and sank.[14]

This underground geology, and the disasters of enterprise incurred there, are easy to forget, until they bubble up and beg attention. It still bubbles today, as the sinkhole created by the accidental piercing is now 35 acres in size, and still growing, still burping up barrels of oil to the surface.[15]